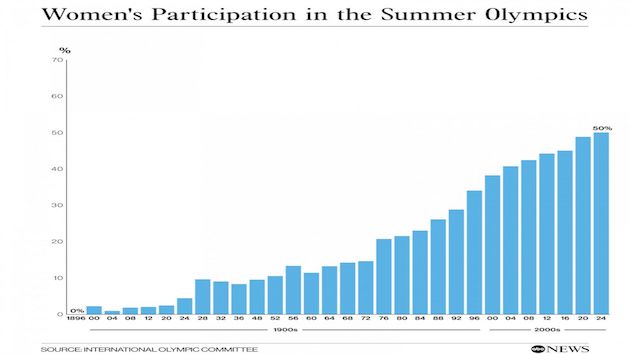

(TOKYO) — At the first modern Olympic Games, held in 1896 in Athens, there wasn’t a single female competitor. When the 2020 Games kick off in Tokyo this month, nearly half of the athletes competing will be women.

Tokyo marks a “turning point” for the elite international sporting competition as the most gender-equal Olympics in the games’ history, organizers said, with women accounting for nearly 49% of the 11,090 athletes. That’s up from 45% at the last games in 2016 in Rio, 23% at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, 13.2% at the 1964 Games in Tokyo, and 2.2% at the 1900 Games in Paris — the first to have female athletes.

When the games return to Paris in 2024, there is anticipated to be full gender parity, with the same number of female athletes as male athletes.

The milestone comes as the 2020 Games have sparked a conversation around the needs of mothers in particular, regarding accommodations around pregnancy, breastfeeding and child care and as scandals involving the abuse and harassment of female athletes continue to plague sports globally.

In the years leading up to the Tokyo Olympics — which, after being delayed a year due to the coronavirus pandemic, run Friday through Aug. 8 — the International Olympic Committee has been working toward achieving more gender equity in terms of athlete quotas and event programming.

Women’s Participation in Summer Olympics

Deliberate action

The IOC was “very deliberate” about working with international sports federations, which are in charge of their discipline’s qualifying procedures, to increase the number of female athletes in 2020, IOC Sports Director Kit McConnell told ABC News.

“We got the overall number of athletes down from Rio to Tokyo, but even in getting the overall number down, we increased the number of women’s athletes,” he said.

For the first time, each team participating will have at least one female and one male athlete, and the 2020 Games will feature new events for women and more mixed-gender teams in an attempt at greater gender equity within sports.

Some events have been dropped for men and added for women in boxing, canoe slalom and rowing, and two more women’s teams will compete in water polo in Tokyo than in Rio, for 10 women’s teams and 12 men’s teams total. In swimming, the 1,500-meter freestyle — an event only men previously competed in at the Olympics — has also been added for women.

The five sports debuting at Tokyo — karate, skateboarding, speed climbing, surfing and three-on-three basketball – will all have women’s events. Both baseball and softball also return to the Olympics after a 13-year hiatus.

The Tokyo Games will have double the number of mixed-gender events than in 2016, for 18 total, including in archery, shooting, judo, table tennis, track and field, triathlon, swimming and surfing.

“We don’t think there’s anything more equal than to have men and women competing in the same team, on truly equal footing,” McConnell said.

The International Judo Federation had pushed to add a mixed-team event, with three men and three women on each team, to the Olympics “for years,” the organization’s spokesman, Nicolas Messner, told ABC News.

“Judo is an individual sport that you have to practice as a group,” he said. “You cannot train alone in judo.”

Having a mixed team was “natural,” he said. And while there won’t be any spectators at the 2020 Games, the event has had an “amazing” atmosphere in other competitions. “The noise level in the venue is way higher during the team event than during the individual competition,” he said.

Additionally, for the opening ceremony, all Olympic teams are encouraged to have one male and one female athlete carry their country’s flag.

Increased visibility for women’s sports

When the games are broadcast, women’s events will also have more visibility in the 2020 Games, with a more balanced schedule on the weekends — including more women’s team gold medal events (17) than men’s (13) on the last weekend — according to McConnell.

“It’s not just about having the athletes on the field of play, it’s also finding the best positions in the schedule to promote those events as well,” he said.

The Olympics are a time when women’s sports often receive their greatest visibility.

“Generally speaking, the coverage of women’s sports is very low, and I think the Olympics is often the exception to that,” Sarah Axelson, vice president of advocacy for the Women’s Sports Foundation, told ABC News.

A 2017 report by the Women’s Sports Foundation found that media coverage of men’s and women’s athletes in the 2016 Olympics was “relatively equitable.”

Having more women in the Olympics has a “ripple effect,” with more investment and equality in other competitions, McConnell said. The Olympics can also create a pathway for professional athletes. In boxing, women first competed in the Olympics at the 2012 Games in London. At Rio in 2016, there were 36 female boxers and three weight categories; that will be up to 100 boxers and five weight categories for Tokyo.

“Where it is now versus where it was 10 years ago … it’s just a night and day change,” McConnell said. “And that’s because now there are medal opportunities, there are qualification opportunities, there are pathways for the athletes.”

Allyson Felix celebrates with her daughter Camryn after finishing second in the women’s 400-meter final at the 2020 U.S. Olympic track and field trials on June 20, 2021 in Eugene, Ore.

Basketball, soccer and softball are other sports that have benefited from an Olympic profile, according to Cheryl Cooky, a professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Purdue University, an editor of Sociology of Sport Journal and the co-author of “No Slam Dunk: Gender, Sport, and the Unevenness of Social Change.”

“I think the Olympics have really, historically for women athletes, served an important role with respect to opportunities,” Cooky said. “There was a time 20, 30 years ago where there really weren’t strong, viable professional leagues for women. You competed in college and then once you graduated, your career opportunities were essentially over for the most part.”

“In some ways, the Olympics are really serving an important function to provide another venue for women to be able to participate,” she said.

More room for improvement

Even as the Olympics are set to have full gender parity by 2024, other areas within the Olympics movement are working toward greater gender equality.

For Tokyo, the Paralympic Games will have at least 40.5% female athletes, up from 38.6% at Rio in 2016.

Over the past decade, only 10% of accredited coaches at the Olympic Summer and Winter Games were women, according to the IOC. The organization has committed to working with international sports federations and national Olympic committees to have more female coaches.

“That’s an area that for the time being is a little bit harder for us to directly control,” McConnell said, noting that the IOC can set athlete quotas, but the athletes ultimately choose their coaches. “But what we can do is put in place programs with the national Olympic committees, with the international federations, and create the opportunities from the bottom up to … develop women’s coaches.”

The IOC has also been working to improve the representation of women within the organization itself, where women currently make up 33.3% of the IOC executive board and 37.5% of IOC members.

Leading up to the games, organizers for the Tokyo Olympics have also faced criticism over comments and policies impacting women.

In February, Yoshiro Mori, then-president of the Tokyo Olympics organizing committee, resigned following backlash over sexist comments he made suggesting women talk too much in meetings. He was replaced by a woman, Seiko Hashimoto, who is a decorated Olympian.

After several breastfeeding athletes spoke out against a pandemic-based policy that banned athletes’ family members from traveling to Tokyo, the organizing committee adjusted its policy to allow nursing mothers to bring their children “after careful consideration of the unique situation” those athletes faced, it said in a statement.

“If we want to support female athletes, part of being a female athlete is also having a family and if you want to support me as a complete athlete, you should be able to make room for my family,” U.S. Olympic marathoner Aliphine Tuliamuk, who gave birth to a daughter in January and fought to bring her still-nursing child to Tokyo, told “Good Morning America” last week. “You can’t just talk about supporting women and then not actually support them.”

The case of Canadian boxer Mandy Bujold also highlighted the unique circumstances facing female athletes with families. Bujold’s Olympic qualifying tournament was canceled due to the pandemic, and she was either pregnant or on maternity leave for the tournaments that ended up deciding the Olympic rankings. The IOC denied her request to have her pre-pregnancy ranking recognized, though Bujold won an appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport and will be competing in Tokyo. The IOC had said in a statement that as a result, it may have to “make decisions that would prove detrimental to other athletes,” though accepted her entry “as a matter of exception.”

These situations, though spawned by unprecedented circumstances, only further highlight the challenges parenting athletes face, Axelson said.

“The circumstances for this year certainly add an extra layer of scrutiny and complexity to it, but it’s a challenge that athletes who are parents, or breastfeeding moms, they will face every year regardless of whether or not we are enduring a global pandemic,” she said. “They’re still a parent, they still have to figure out how to train and compete with a child.”

Earlier this month, the Women’s Sports Foundation and Athleta announced a program that commits $200,000 to help fund child care costs for professional mom-athletes who are traveling to competitions. The first recipients of the Power of She Fund, who will each get $10,000, include six athletes headed to the Tokyo Olympics.

“Parenthood should not be the barrier to athletic participation or athletic success,” Axelson said.

For Cooky, it’s challenging to talk about progress in gender equality when women are sometimes subjected to “problematic dynamics as a part of their participation,” such as abuse.

Between the Rio and Tokyo Olympics came allegations of sexual abuse against former USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar from dozens of girls and women. Nassar pleaded guilty in 2017 in a case that made international headlines as prominent gymnasts, like gold medalist Aly Raisman, read emotional statements during sentencing. Basketball’s world governing body, FIBA, is currently investigating allegations of systemic sexual abuse of female players in Mali, as first reported by The New York Times.

“Women’s sports have made some important strides over the last 40, 50 years, but at the same time, there’s a lot of challenges and discrimination and inequality and abuse,” she said. “We have to take those into account as well, because otherwise we’re not telling the complete story.”

Copyright © 2021, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.